Editorial: Wound Round With Mercy

Intimations of Divine Love

Every nursing mother knows what it is like to be dragged out of desperately-needed sleep, night after night, by insistent crying. Faith B. was no exception. The received wisdom of the time made matters harder by forbidding the comforting, common-sense practice of having the baby sleep in one's bed, so there was nothing for it but to half-fall out of bed and stumble in the general direction of the nursery. One particular night seemed to be only more of the usual; she remembers grazing the doorway on her way in. But she had no more than settled into the familiar nursing routine when the heavens opened. Exhaustion melted away before a flood of unutterable joy and power and love. She became aware of an everywhere-present Divine Mother nurturing all beings in the world, cradling them with infinite tenderness; furthermore, she knew that she was in the midst of this process, both receiving abundant life and giving it. She found herself murmuring ecstatically "I feel like a goddess! I feel like a goddess!"

The person who undergoes such an experience does not doubt its truth to reality as it is happening, and for some time afterwards. Unless s/he has experiences of this sort repeatedly (and Faith had several), however, its powerful impact may diminish over time. But if the experiencer reflects upon it often, reaffirming her first conviction of its truth, exploring its meaning, and acting upon its implications, it may come to shape the entire course of her life.

Darkness and Cold

But what of those who never have such a lifegiving experience, or have numinous experiences that seem to give quite a different message? As William James remarks, a religious experience is not necessarily authoritative for those who have not had it. One can point out that there are all too many facts that seem utterly incompatible with Faith's sense of the presence of an all-nurturing Divine Mother. To give just one example: In eighteenth century London, an estimated one thousand infants were abandoned on the streets every year by desperate unwed mothers unable to support them, mothers themselves abandoned by lovers whom society essentially excused from taking responsibility. A parallel situation can be found in the ancient Roman world; according to law, the paterfamilias had the right to decree that any newborn he chose not to accept must be thrown out, exposed. (The abandoned babies were sometimes "rescued" by slave traders.) How can one say that these innocents, dying of cold, hunger, and fear, were nurtured by an all-loving and all-giving Divine Mother?

But what of those who never have such a lifegiving experience, or have numinous experiences that seem to give quite a different message? As William James remarks, a religious experience is not necessarily authoritative for those who have not had it. One can point out that there are all too many facts that seem utterly incompatible with Faith's sense of the presence of an all-nurturing Divine Mother. To give just one example: In eighteenth century London, an estimated one thousand infants were abandoned on the streets every year by desperate unwed mothers unable to support them, mothers themselves abandoned by lovers whom society essentially excused from taking responsibility. A parallel situation can be found in the ancient Roman world; according to law, the paterfamilias had the right to decree that any newborn he chose not to accept must be thrown out, exposed. (The abandoned babies were sometimes "rescued" by slave traders.) How can one say that these innocents, dying of cold, hunger, and fear, were nurtured by an all-loving and all-giving Divine Mother?

Readers of PT will also think of the millions of terrified infant animals torn from their anguished mothers--or never even seeing them--and shipped to confinement and violent death, in order to overload a table at which sit unthinking and (often) unhealthy human beings. The human mind cannot comprehend how an all-nurturing deity can be any part of this dreadful picture. Mind is stopped by Mystery.

This conflict between faith in the embrace of the divine Mother and the suffering of little ones is, of course, only one version of the problem of evil that has bedeviled people who take seriously both religious intuitions and painful facts. Since the intuitions are so much harder to establish publicly than the facts, why should those who do not have the intuitions trouble themselves with what they imply?

"Is the Universe Friendly?"

One answer has to do with the way our worldview tends to influence us in shaping that world, especially when a long period of time is in question. Before explaining this statement, I must acknowledge that there are some people who would answer William James' question "Is the universe friendly?" with a firm "No"--there is no unseen Love that cares for us all--but who nonetheless devote their energies to awakening that world and making it a kinder place. Such a one was Marian Evans, better known as George Eliot, who in her late teens underwent the calamity of losing her faith. She deals with the loss-of-faith issue in her poignant novel Silas Marner, which centers on a snowy night in Christmastide when an orphaned child toddles into the home and heart of a desolate weaver. Surprisingly, the story seems to give the last word to unseen Love. A more mundane personal example: I remember, from years ago, that the avowedly atheistic mother of one of my daughter's elementary school friends was willing to take charge of the school's annual fundraising fair, on the condition that it would have a Peace theme. It was well done. She and I have long been out of touch, and I wonder occasionally if she is still organizing Peace Fairs or doing good work of a similar sort. I very much hope so.

I suspect that such admirable folk are exceptions, however--that most of those who work in some way to help repair and heal the world are motivated by a conviction that by doing so they are attuning their lives and their surroundings to ultimate Reality. Depending on their worldview, typically Eastern or typically Western, they may feel they are helping to realize a Oneness that underlies all things despite multiple conflicts; or that they are heeding the mandate to be compassionate as their all-parenting God is compassionate. In Quaker language, which has something of both outlooks, they are opening their hearts and hands to the divine Light that is Love present in every being.

I suspect that it is when efforts to bring about transformation and healing are repeatedly blocked that the importance of this faith in the deep "Friendliness" of the universe, of ultimate Reality, comes into play. It is hard to sustain the doggedness necessary for a long struggle unless we have this sense that we are ourselves sustained in the work of transformation--that Love transcends our individual efforts to realize love.

The Lost and the Foundlings

To return to the abandoned babies of London: in 1719 one Thomas Coram, who had had a successful career in the American colonies and at sea, came back to England. His expectations of enjoying the good life were brought up short by the horrifying scenes of dead and dying babies that he saw as he walked London streets on a cold winter morning. A man of action as well as compassion, Coram set about establishing an organization to rescue such victims. There was much accumulated wealth in the hands of the middle and upper classes, and he hoped to reach their hearts for his project.

To return to the abandoned babies of London: in 1719 one Thomas Coram, who had had a successful career in the American colonies and at sea, came back to England. His expectations of enjoying the good life were brought up short by the horrifying scenes of dead and dying babies that he saw as he walked London streets on a cold winter morning. A man of action as well as compassion, Coram set about establishing an organization to rescue such victims. There was much accumulated wealth in the hands of the middle and upper classes, and he hoped to reach their hearts for his project.

To us today, this seems the sort of plan everyone would approve. But Coram ran into resistance, deep-seated and determined, from men who found the project threatening to their privileges and to social structures. The gist of it was: these babies were, were, after all, only bastards! To make provision for them would be to break down the safeguards of female purity; it would encourage young women to a life of vice. . . There was no equivalent anxiety about male purity, needless to say. Some dismissed the whole thing with cynical and amused speculations about Coram's motivations. No doubt he had himself taken many a tumble in the hay, said one wag, and now wanted to salve his tender conscience regarding the results.

Coram must have been hurt and outraged by such callous reactions, but he was not defeated. He worked doggedly, year after year, with the help of artist William Hogarth and others. One of the strategies they developed was to appeal directly to wealthy women, including the Queen Caroline, consort of George II, who became concerned and wrote a pamphlet on the subject. Another was to garner the support of painters and musicians. After twenty long years, in 1739, a milestone was passed: Coram and colleagues were granted a royal charter to build an orphanage, or "Foundling Hospital." Years of fundraising, building, and other work still lay ahead, but the doors of the Hospital's first structure opened in March, 1741. The Hospital could take in far fewer than half of the infants abandoned in London each year. But it was a beginning, a presence, an influence on the mind and heart of English society. (The Hospital closed its doors in the twentieth century, but in its present form, called the Coram Family, it still supports families with children at risk.)

"Blessed Are They . . ."

I do not know whether Thomas Coram was sustained in his years of heroic labor by faith in divine compassion, or whether he perceived himself as trying to kindle light and warmth in an ultimately dark and cold universe. But there is no doubt that some of his supporters had such faith. One was the composer Handel, not a saint, but a large-hearted, compassionate man who donated an organ to the Hospital's chapel and wrote a suite of inspired anthems based on the Psalms for the chapel's dedication. The texts situated the Hospital's work firmly in the context of the Jewish and Christian vision of God's love for the lowest and least. "Blessed are they that considereth [sic] the poor and needy; the Lord will deliver them in time of trouble. . . " with "them" probably referring, in listeners' minds, both to the donors and the babies. Handel also gave a benefit performance of Messiah every year, garnering, over nearly a decade, about a million dollars in today's money for the Hospital (and assuring immortality for his oratorio). No doubt a good number of the listeners were worldlings whose conscious interest was only in enjoying Mr. Handel's delicious music. But there were probably some, genuinely devout, who connected its central section on the birth of the poverty-stricken Divine Child with the foundling babies. Perhaps some listeners also linked arias such as "He Was Despised" with the contempt that had so long surrounded "bastards."

The problem of how all-embracing Divine Love can coexist with a situation in which thousands and millions of innocents continue to be victimized by callous resistance to compassion is, of course, still unsolved. But a willingness to live with the Mystery, and continue to affirm the ultimate reality of unseen Love, can empower us to persist in the face of blind opposition. In the bleak midwinter, it can help us bring that love to earth.

Peace on Earth, good will to all.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

orpHospitalrelieverelievethe importance

Inti Wara Yassi's website: www.intiwarayassi.org/articles/volunteer_animal_refuge/home.html

Animales SOS: www.animalessos.org/pag/english/index_e.html

e-mail addresses

the e-mail address for the IWY website (English or Spanish okay) : intiwarayassi@gmail.com

Juan Carlos and Nena Balthazar (speak mostly Spanish) : ciwy99@yahoo.com,

Johnny and Luis Morales, the vets at the park (speak a little English, mostly Spanish) : jhonny.d.l@hotmail.com, lumor23@hotmail.com

Pea Macpherson who is coordinating efforts to save the park (speaks English) : peamacpherson@gmail.com

Paola, a semi-permanent volunteer at the park (Speaks only Spanish) : lucianyta@hotmail.com

My own e-address: bandittinkerpirate@gmail.com

also if you're on facebook, look up Andre Jimenez Gomez, who has been particularly helpful and speaks English.

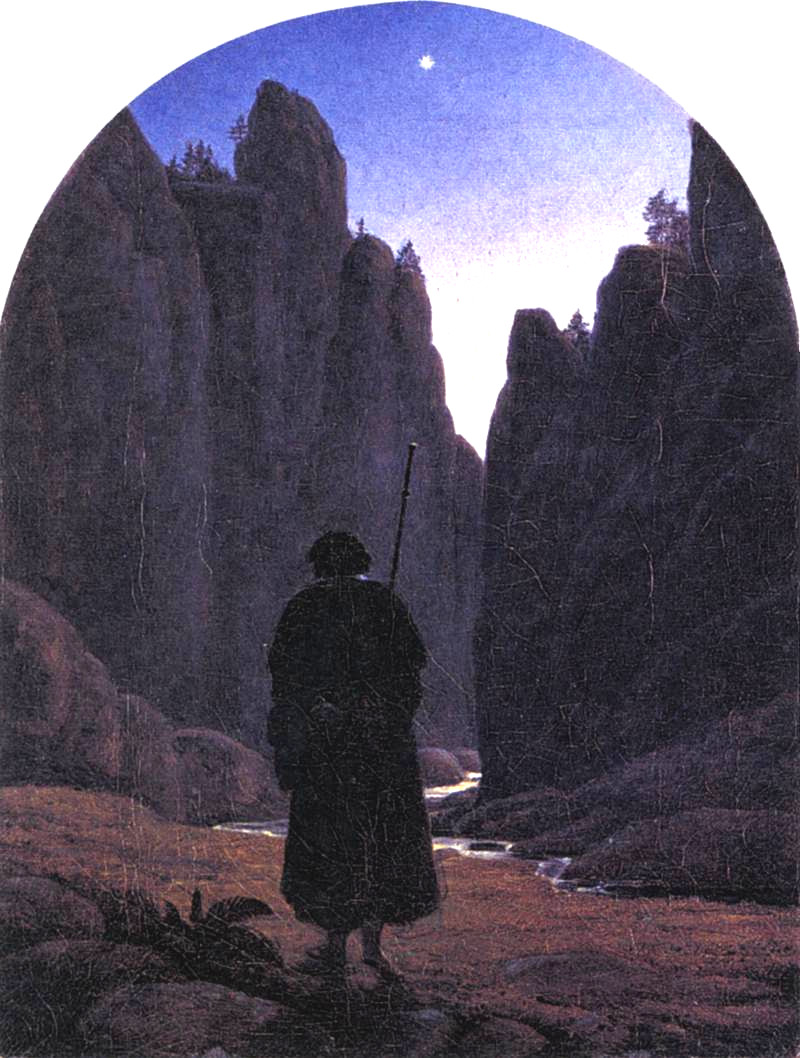

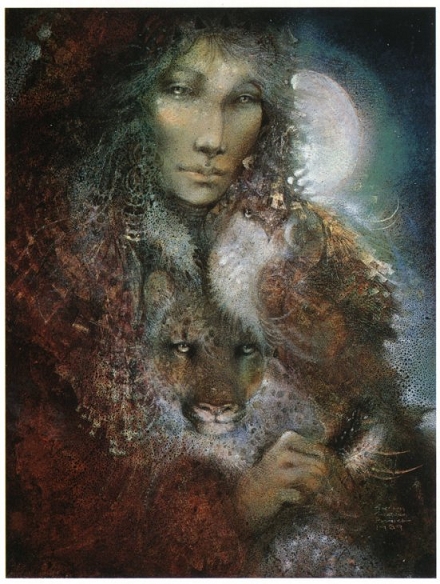

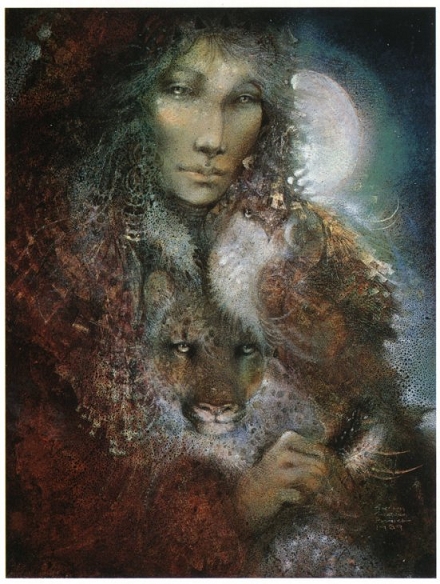

Painting of madonna with child and lamb, entitled "Innocence," is by William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Painting of woman with moon and leopard by Susan Seddon Boulet. Painting of Thomas Coram by William Hogarth.

We invite responses to editorials or any other feature of PT for our next issue's letter column: graciafay@gmail.com.

News Notes

Californians Pass Anti-Cage Proposition

On November 4, Proposition 2 was approved by an overwhelming margin in California, a historic step in the direction of ending the inhumane confinement of animals on factory farms. Although the changes it mandates are relatively small, it is of great symbolic importance. Wayne Pacelle of the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) expresses it well by saying, "California voters have taken a stand for decency and compassion and said that the systemic mistreatment of animals on factory farms cannot continue. . . . " The measure goes into effect in January of 2015, but changes should come before that. To read the full article see www.hsus.org/farm/news/ournews/prop2_california_110408.html.

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

In Planning: Web of Death

Tom Philpott, founder of Maverick Farms, a sustainable-agriculture non-profit and small farm located in North Carolina, writes of Tyson Foods, the monster US animal-processing firm, that it is planning to expand to Brazil, India, China, and the entire global south. Tyson was the innovator of the "vertical-integration" strategy that now dominates "meat" production: they own breeders and slaughterhouses, leaving the risks of raising the animals to farmers working on contract. Philpott rightly says that Tyson is "actively pursuing a nightmare vision for the globe." To read the full article see "Meat Wagon: All the World's a CAFO [Confined Animal Feeding Operation]." gristmill.grist.org/story/2008/11/10/13149/672/

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Book Review: The Hopes of Snakes & Other Tales from the Urban Landscape

Lisa Couturier. The Hopes of Snakes & Other Tales from the Urban Landscape. Boston: Beacon Press, 2005. $14.00, Paperback. xiv + 159 pages.

Lisa Couturier - environmental journalist, magazine editor, teacher --here writes movingly about the wildlife that can be found in the hidden wild spaces of the northeastern megalopolis stretching from Washington, DC, to New York City. It seems tremendously counterintuitive that such an abundance and variety of wild animals could manage to survive, and even thrive, in one of the world's most thickly urbanized areas. Yet here they are: owls, hawks, mice, pigeons, foxes, beavers, crows, snakes, geese, coyotes, vultures, and many others. Lisa loves them and knows that they are beings with hopes and dreams, with loves and families. She does not feel the contempt, fear and hatred that is all too common among humans towards these creatures.

Lisa Couturier - environmental journalist, magazine editor, teacher --here writes movingly about the wildlife that can be found in the hidden wild spaces of the northeastern megalopolis stretching from Washington, DC, to New York City. It seems tremendously counterintuitive that such an abundance and variety of wild animals could manage to survive, and even thrive, in one of the world's most thickly urbanized areas. Yet here they are: owls, hawks, mice, pigeons, foxes, beavers, crows, snakes, geese, coyotes, vultures, and many others. Lisa loves them and knows that they are beings with hopes and dreams, with loves and families. She does not feel the contempt, fear and hatred that is all too common among humans towards these creatures.

The chapter on vultures is particularly fine. These birds are much maligned, though they perform such a useful function. Humans who appreciate--let alone love--vultures are few and far between. The facts that they are social, beautiful in flight, and benefit everyone are lost in human-imposed symbolism: they might as well be shadowy figures wearing black cloaks and carrying scythes. At least, however, they have a beautiful scientific name in Latin: Cathartes aura, "Cleansing breeze." In pointing this out, as elsewhere in her book, Lisa Couturier demonstrates that poetry and science can be harmonious.

One of the best of the fourteen essays in the book, and my favorite, is the tenth (pages 87-100), in which she narrates how a human mob at an Oktoberfest was threatening to kill a huge black Rat Snake - a species that looks very frightening to many humans, but is perfectly harmless to us. Couturier, having been trained on how to pick up and carry a snake, saved the beautiful creature from death and carried her or him to safety. To cite (and improve on) Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Battle Hymn of the Republic," "Let the hero born of woman save the serpent with her hands."

The common human attitude toward snakes as sinister representatives of Evil is another example of the symbol virtually devouring the reality. Symbols in many cases can enrich our lives, but we must reject their influence when they close our hearts to our fellow beings and encourage fear and cruelty. Reading books like Lisa's helps us to see and cherish the animal world as it really is, a stance very important for spiritual growth. I strongly recommend this poetic and educational book to all who love animals--or are willing to begin.

--Benjamin Urrutia

Book Review: The Blessing of the Beasts

Ethel Pochocki, The Blessing of the Beasts. Engravings by Barry Moser. Brewster, Massachusetts: Paraclete Press. 2007. Hardbound. 40 pages, $18.95.

This tale is a fantasy that will warm the hearts and inspire the minds of both children and grownups who love animals. It tells the story of an unusual celebration of the Blessing of the Animals - an event that in real life takes place in many churches of various denominations on the Feast Day (October 4) of St. Francis of Assisi, that most Christian of Christians, who rightly saw all God's creatures as our brothers and sisters.

This tale is a fantasy that will warm the hearts and inspire the minds of both children and grownups who love animals. It tells the story of an unusual celebration of the Blessing of the Animals - an event that in real life takes place in many churches of various denominations on the Feast Day (October 4) of St. Francis of Assisi, that most Christian of Christians, who rightly saw all God's creatures as our brothers and sisters.

The story begins comically, with inner-city cockroaches carrying the news of the upcoming celebration to the resident roaches at the St. Francis Soup Kitchen. The first three illustrations are of the roaches - in close-up, and in cartoonlike anthropomorphic style. The third one is of Francesca (born in the soup kitchen and named after the saint) - a rare depiction of an appealing and sympathetic roach. Except for Francesca, the heroine of the story, the roaches soon vanish from both the narrative and the illustrations, and the style becomes very realistic, almost photographic. This might be seen as a defect by critics who insist on the Aristotelian Unities. Personally, it did not diminish my enjoyment of the book's beautiful message and magnificent art.

Francesca soon persuades her friend Martin (named after another animal-loving saint, Martin de Porres), to travel with her to the Feast of Blessing. Martin fears that only animals who are considered cute and cuddly will be welcome at the celebration: "We are outcasts, my dear." She persuades him to go with her anyway and stand at the back, and they make the trek. Happily, an elephant in the animal procession gives them a ride to the altar. Happily, too, the Franciscan in charge of the event (a self-portrait of artist Barry Moser), is a true disciple of Jesus and Francis. He acknowledges and blesses them, thus teaching that God loves us and blesses us all, regardless of how popular we are or many legs we have.

The illustrations depict the beauty of God's creatures, including, not accidentally, Martin the skunk. There are four of cats and kittens, who are the ones closest to my heart of all God's Creation.

-Benjamin Urrutia

Book Review: Alex and Me

Irene M. Pepperberg, Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence -- And Formed a Deep Bond in the Process. New York: Collins/HarperCollins, 2008. 232 pp., $23.95. Hardcover.

This remarkable book -- a national bestseller -- begins and ends with the same grief, the death of Alex, the African Grey parrot who had been the author's companion and research associate for some thirty years. The story then circles back to show us why the passing of this little creature devastated not only Irene Pepperberg, but also his millions of fans throughout the world, admirers of the numerous popular features in print and on television in which he had starred. Early on, we learn of the author's emotionally deprived childhood; her failed marriage, her ricochet academic career as one institution of higher education after another proved unable or unwilling to accommodate her pioneering project, the great passion of her life: Alex and what he was teaching the world about animal intelligence.

This remarkable book -- a national bestseller -- begins and ends with the same grief, the death of Alex, the African Grey parrot who had been the author's companion and research associate for some thirty years. The story then circles back to show us why the passing of this little creature devastated not only Irene Pepperberg, but also his millions of fans throughout the world, admirers of the numerous popular features in print and on television in which he had starred. Early on, we learn of the author's emotionally deprived childhood; her failed marriage, her ricochet academic career as one institution of higher education after another proved unable or unwilling to accommodate her pioneering project, the great passion of her life: Alex and what he was teaching the world about animal intelligence.

And what Alex taught her was indeed astounding, well beyond what most scientific authorities of the time were willing to accept. Barrier after barrier long thought to separate human from animal intelligence fell before the one-pound parrot's walnut-sized brain as he showed, in experiments conducted in accordance with rigorous scientific standards, that he could name objects, generalize, count, identify colors by number, play creative tricks, even come up with the concept of zero, which as Pepperberg says "had eluded the great Greek mathematician Euclid of Alexandria." A detailed account of the research is given in the author's other book, The Alex Studies (2000).

Another dimension of Alex's mind was shown one day in 1998, when Irene Pepperberg stormed into the lab room very upset after a difficult academic meeting. The parrot, clearly able to pick up clues to her feelings, saw her and said "Calm down." Though she would otherwise have found this comment from a bird extraordinary, Irene, who was in no mood to live up to her first name, admits she did not respond accordingly but snapped, "Don't tell me to calm down!" and slammed into her office.

Another dimension of Alex's mind was shown one day in 1998, when Irene Pepperberg stormed into the lab room very upset after a difficult academic meeting. The parrot, clearly able to pick up clues to her feelings, saw her and said "Calm down." Though she would otherwise have found this comment from a bird extraordinary, Irene, who was in no mood to live up to her first name, admits she did not respond accordingly but snapped, "Don't tell me to calm down!" and slammed into her office.

Alex & Me will surely hearten those with deep concern for the humane treatment of animals and who harbor a vital sense of the kinship of all life. To a great extent Pepperberg herself shares these concerns, and her work is infused with awareness of the wonderful mystery of animal consciousness. In one of the finest passages in the book, she writes:

Alex's sudden, unexpected departure left me in awe at his achievements and wondering what else he would have done had he stayed. He left at the height of powers. To some what he did seemed magical, or at least otherworldly. Indeed, he had given us a glimpse of another world, one that had always existed but remained beyond our view: the world of animal minds. (p. 213)

(If I may digress for a moment, the thought occurred to me that, given what is now generally accepted of the close relationship between the birds of today and the dinosaurs of yore, could it be that the latter were far more intelligent, even communicative, than the usual stereotype: What if the only reason they failed to move into what we are pleased to call civilization was not lack of brains but of hands? Many years ago I had a strange dream in which I somehow time-traveled back to the time of the dinosaurs and saw evidence of their great intelligence, but was then given to understand this was something I was not supposed to have seen.)

Nevertheless, although Pepperberg speaks eloquently on behalf of the decent treatment of parrots and other animals, with a profound feeling for their emotional and mental lives, her position in regard to animal rights is surprisingly ambivalent. Saying that "Some people take this new understanding of animal minds as an argument for treating animals as if they had the same rights we give to ourselves,"she responds, "That is as wrong as the behaviorists' restrictive gospel." (p. 221)

Of course in our present anthropocentric society it would hardly be possible for animals to hold the same political rights as humans. It would be meaningless, for example, to give them the right to vote. But a deep understanding of what is rising into human consciousness through the work of Pepperberg, Jane Goodall, Marc Bekoff and others on the rich world of animal consciousness could change the picture in some future generation. One with a prophet's vision might even now foresee most of the U.S. Bill of Rights, together with the abolition of slavery amendment, extended with compassionate imagination to all sentient beings in some form -- freedom of assembly with their kind, freedom from enslavement and violence. But that new Eden would require attitudinal and lifestyle changes, including changes in human diet, with which Irene Pepperberg -- for all her splendid insights -- seems not yet prepared to engage. Considering how revolutionary the picture is that she has drawn of bird consciousness, she may be wise to go no further at present.

This whole amazing animal intelligence world now being uncovered calls for much new thinking on the part of all of us. As we approach those emergent thresholds of human thought, we can only be profoundly grateful for what Irene Pepperberg, and other like her, have done to open our minds and hearts.

--Robert Ellwood

Gems

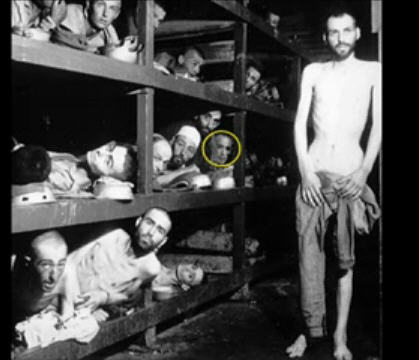

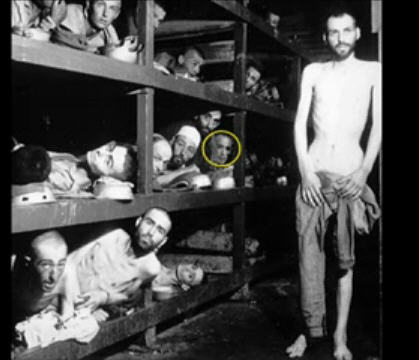

From concentration camp survivor and novelist Elie Wiesel: "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented."

From concentration camp survivor and novelist Elie Wiesel: "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented."

--Contributed by Steve Kaufman

To shut your mind, heart and imagination from the sufferings of others is to begin slowly, but inexorably, to die. Those Christians who close their minds and hearts to the cause of animal welfare, and the evils it seeks to combat, are ignoring the fundamental spiritual teachings of Christ himself."

~ John Austin Baker, Bishop of Salisbury, England 1982-1993.

Sermon on the World Day of Prayer for Animals, 4 October 1986.

Letters

Thanks for the inspiration of your newsletter. The newsletter helps us to support one another, . . .heal, grow, and help one another.

[In regard to the] review by Benjamin Urrutia of the cartoon movie Space Chimps, I found a site dealing with the original space chimps at "Save the Chimps": www.savethechimps.org. I think that it is important to understand what these darling children of God currently need. It may help wake people up to a stronger sense of the urgency of animal rights and service, if one were take a look at what our precious chimps, that had been in space, or any laboratory or program, have been through. . . .

--Michele Louise Mitchell

Recipes

Vegan Chorizo (Spicy Spanish Vegan Sausage)

makes about 1 pound

½ recipe Seitan Rosa

For the recipe for Seitan Rosa, see Feb. 2007 PT.

2 tsp. sesame oil

1 T. extra virgin olive oil

2 T. sherry vinegar

1 T. finely minced garlic

1 T. paprika

1 ½ tsp. dried oregano

1 ½ tsp. ground cumin

¼ tsp. ground cayenne, or to taste

¾ tsp. sea salt

½ tsp. freshly ground black pepper, or to taste

¾ cup vital wheat gluten (adjust amount so that the sausages hold their shape when handled)

Drain Seitan Rosa after simmering in cooking broth. Place Seitan, sherry vinegar, sesame and olive oils, garlic, paprika, oregano, cumin, cayenne pepper, salt and pepper in food processor bowl. Process until well chopped and appears like sausage.

Place in a medium mixing bowl. Stir in vital wheat gluten a little at a time until the Seitan holds its shape and can be made into “sausages” about 2 inches long and about as thick as your thumb. Makes 14 - 18 sausages.

Gently steam the sausages in the basket of a steamer on top of the stove for 20 minutes. Do this in at least two, possibly three, batches to avoid overcrowding.

Remove basket and let sit a couple of minutes, then place Seitan sausages in a glass bowl. Continue until all Seitan sausages have been steamed.

They may now be sautéed in olive oil or frozen until ready to use in a recipe. When thawing, remove from freezer and allow to thaw in refrigerator or at room temperature.

Freeze the other half of the Seitan for later use or make another variety of sausage and freeze.

Vegan Chorizo is the veganized version of the very spicy Spanish sausage. It is delicious when grilled after the steaming process.

--Angela Suarez

Rice Pudding

serves 4

1 quart soy milk, vanilla flavor

1 cup arborio rice

½ cup dried fruit (such as currants, cranberries, cherries, or raisins)

2 T. Earth Balance Buttery Substitute

¼ cup evaporated cane juice (organic sugar)

2 tsp. grated organic orange zest

1 tsp. organic vanilla extract

freshly grated nutmeg, to taste

1 pint organic strawberries, cut into quarters

In a medium size sauce pan, bring soy milk to a boil. Add arborio rice, stir well; reduce heat to maintain a slow simmer. Continue to cook, stirring frequently, until the soy milk has been absorbed, about 30 minutes. Just as the rice is finishing cooking, stir in the Earth Balance, organic sugar, orange zest, vanilla and nutmeg. Stir well and serve immediately in individual bowls. Top each serving with fresh strawberries.

--- Angela Suarez

Sea Veggie Burgers for Canine &/or Feline Friends

makes about 1 - 1 ½ dozen patties

1 cup chopped Seitan (See Basic Seitan recipe which follows)

1 cup brown rice, cooked

2 T. nutritional yeast

1 tsp. powdered kelp

1 tsp. dried dill weed

½ cup soy milk

1 cup organic whole wheat flour, or as needed to hold patties together

extra virgin olive oil for brushing surfaces of patties

Preheat oven 400° F.

In the bowl of a food processor, place Seitan, rice, nutritional yeast, kelp, dill and soymilk; process until well mixed. Spoon out into a medium size mixing bowl; stir in flour to form a dough from which patties can be shaped. It will be easier to shape patties if hands are wet. Place patties on a well-oiled baking sheet and brush their tops. Bake 10-12 minutes. Remove from oven, turn patties over, brush with olive oil. Return to oven and bake 10 -12 more minutes until crisp. Once all patties have baked, allow to cool in oven. Serve when cooled to room temperature. Store in refrigerator in tightly covered container.

These are a very nutritious biscuit. Companion animals, both dogs and cats, love the taste of sea vegetables. This recipe uses kelp powder.

--Angela Suarez

Basic Seitan (for Companion Animals)

makes about 1 ½ pounds Seitan

2 cups vital wheat gluten

2 T. nutritional yeast

1 tsp. Tamari or soy sauce or Bragg’s liquid aminos

1 T. tomato paste

½ tsp. powdered rosemary

1 ½ cups spring water

4 - 4 ½ cups simmering water

Place all ingredients in the bowl of a food processor. Process until a ball of dough forms. Remove from processor. Using a serrated knife, cut the dough into pieces and work a bit in your hands. This helps to prevent the Seitan from expanding too much during cooking.

Place Seitan pieces in a large pot of simmering water. Simmer for 1 ½ - 2 hours. The Seitan will expand and shrink again during the cooking process. Do not boil, but maintain a gentle simmer.

--Angela Suarez

Pioneer: Dorothy Tucker Samuel, 1918 - 2001

Vegetarianism and Friends

My experience with vegetarianism has gone through many phases. One of the most disturbing has been the response of Friends to this practice.

My experience with vegetarianism has gone through many phases. One of the most disturbing has been the response of Friends to this practice.

As a child, I had several times attempted to eliminate meat from my diet out of concern for the animals who lived only to die, sometimes in agony, to supply that diet. I was always persuaded out of it by my mother who spoke for the environment in which I was raised. It was the unalterable conviction of health professisonals as well as ordinary people that one could not be nourished adequately without animal protein. Were this true--and how often Jesus' catch of fish was quoted!--then God had established a world wherein animals as food were necessary to human survival.

I had barely heard of Quakerism, but had become considerably more sensitive to the actual Gospel, when matters came to a climax in my own spirit. Penn might have said that I had "worn" carnivorousness as long as I could. Pregnant with my last child, I simply woke one morning and knew that I would not again eat flesh. At this time, 1947, I still believed with the world around me that I would pay a price in physical well-being. I soon found the response to that concern in the worlds of Gandhi who said, when told his wife could not live without beef broth, "There are some things a man (sic) won't do just in order to live." It was that quotation which brought my husband into full vegetarianism with me. Only slowly did we discover that our health actually improved rather dramatically and that our four children grew up considerably more healthy than their friends. In time, we also discovered the scientific evidence for these physical benefits, and the tremendous impact widespread vegetarianism might have upon world hunger. But all of that unfolded slowly.

When Quakerism first entered our consciousness as a response to the spirit as well as the letter, as a recognition of continuous revelation, as a guardian of the light of God within each individual, we naively expected it would also be a faith open to tenderness toward all living creatures. Because my husband had already gone into the ministry, it was many years before rejection of the [professional] ministry and geographic location made possible our actual entrance into Quaker fellowship. We approached our first Quaker meeting, in 1959 or '60, with all the unrealistic expectations of spiritual utopia that now frighten us in new attenders. Most of these expectations were fulfilled, however, because we were fortunate to attend first a Quaker group which really approached its divisions and differences in the Quaker spirit. Each problem within the meeting provided a living example of Friends' respect for each other and for the spirit working among us all. . . .

But we were vegetarians and Friends had no more personal or intellectual acquaintance with vegetarianism than any other group of people. What really hurt was that Friends, with exceptions, were more offended by vegetarianism than the beef and sheep growers among whom we lived or the members of conventional churches with whom we had been worshipping. Friends accepted us personally, as they accepted even an occasional soldier or moderate racist. They welcomed us eagerly for our participation in the peace and social justice concerns of the day. At times, I almost felt that their consciences must be more tender to produce such a marked resistance and even repugnance. It was as if they felt their own ethical stance was being attacked by our mere practice. We felt, at the time, that it was futile to talk about not killing animals until the human race could stop killing human beings. We did not attept to change others, and only discussed our practice when it was directly questioned. The practice, however, did stand out in every gathering.

In time we moved, our experience of Quakerism broadened and enlightened [during residence] in two other states. We grew closer to Friends as individuals and as the group expressions of faith in action. But until the youth movement introduced vegetarianism as a lifestyle that could not be ignored, we always found a sense of being loved and approved "in spite of our peculiar idiocy."

In time we moved, our experience of Quakerism broadened and enlightened [during residence] in two other states. We grew closer to Friends as individuals and as the group expressions of faith in action. But until the youth movement introduced vegetarianism as a lifestyle that could not be ignored, we always found a sense of being loved and approved "in spite of our peculiar idiocy."

Today, of course, everyone has heard of vegetarianism. Almost everyone has tried it or knows intimately someone who has tried it. In many ways, I still feel a peculiar person among these knowledgeable folk, Friends and non-Friends. I have been invited to speak and lead groups and write about vegetarianism, but always from the rationale of health, economy, or food production. Outside of my own family, I do not know personally a single ethical vegetarian, although I know many health vegetarians . . . .

My experience of becoming a Friend has been, and continues to be, the greatest support and enlightenment in my life. In my vegetarianism, to quote an old hymn, I feel "near to the heart of God." I wish that the two blessings were closer together, but I treasure both. And it is good that I am no longer suspect among Friends for my vegetarian convictions.

Reprinted from The Friendly Vegetarian, Seventh Month, 1983. Used by permission of the editor and Bill Samuel.

My Pilgrimage as a Lifelong Vegetarian

by Bill Samuel

My experience as a vegetarian begins as told by my mother, Dorothy T. Samuel, whose article of a quarter century ago in The Friendly Vegetarian is reprinted in this issue of The Peaceable Table. I am her last child, and it is when she was pregnant with me that she became vegetarian.

My experience as a vegetarian begins as told by my mother, Dorothy T. Samuel, whose article of a quarter century ago in The Friendly Vegetarian is reprinted in this issue of The Peaceable Table. I am her last child, and it is when she was pregnant with me that she became vegetarian.

Since my mother was a vegetarian when I was born, I was raised vegetarian. Meat never seemed like food to me. We grew up mostly in rural America, and generally we knew of few or no other vegetarians in the communities in which we lived. We didn't go out to eat much, partly to save money, but also because it was hard to get something to eat in restaurants where we lived as almost all entrees included meat.

Vegetarianism was just a part of the complex of issues, based on faith, which made my family different from most of those around us. In the McCarthy era in which I grew up, being pacifist made us highly suspect. And growing up largely in communities which were all white or segregated, our belief in the equality of all humans across ethnic lines was not only unusual, but sometimes a very dangerous belief to hold. In my senior year in high school, in the first year of token integration in the southern Virginia community to which we had moved, all of my friends in school were African-American and only one white student would speak to me other than to insult me. So my vegetarianism was not the biggest obstacle to my being socially accepted.

I did grow up around animals of other species. Stray cats and dogs sometimes found us, and we would accept them in. For a significant part of my childhood, we had a small goat herd. And for much shorter intervals, we had a cow once and a donkey once. I always enjoyed the animals. To me, they were companions in our lives and the idea of doing harm to them was repulsive.

Theologically, I still see vegetarianism as part of the same complex of issues which made my family strange when I grew up, I see in the early part of Genesis glimpses of God's vision for how we should live, which includes giving us plants as our food. I see in the prophets, notably in Isaiah's Peaceable Kingdom passage, a vision of a future day in which that vision would be lived out. Again, the vision includes no creature harming another. I see Jesus Christ as calling us and enabling us to live within that vision within the larger society that is still rebellious against God.

I spent most of my adult life in the Religious Society of Friends. My mother comments that she often found lack of acceptance of vegetarianism among Friends. In the East where I have lived my adult life, vegetarianism has been more common among Friends than in the general population. Still, most Friends are not vegetarian, and unkind jokes about vegetarians were not uncommon among Friends.

At the church where I am now, both the Senior Pastor and the Chair of Trustees are vegetarian. However, the proportion of vegetarians in the congregation is probably not much different than among Friends. But omnivores are more universally respectful of vegetarianism than among Friends.

I see myself called as a follower of Jesus Christ to live more fully in the vision of a Peaceable Kingdom. Vegetarianism is an integral part of that.

Poetry

There is in all visible things an invisible fecundity,

a dimmed light,

a meek namelessness,

a hidden wholeness.

This mysterious unity and integrity is Wisdom,

the Mother of all, Natura naturans.

There is in all things an inexhaustible sweetness and purity,

a silence that is a fount of action and joy.

It rises up in word-

less gentleness and flows out to me from the unseen

roots of all created being, welcoming me tenderly,

saluting me with indescribable humility.

This is at once my own being,

my own nature, and the Gift

of my Creator's Thought and Art within me, speaking

as Hagia Sophia,

speaking as my sister, Wisdom.

I am awakened, I am born again at the voice of this,

my Sister,

sent to me from the depths of

the divine fecundity . . . .

Sophia is the mercy of God in us. She is the tenderness

with which the infinitely mysterious power of pardon

turns the darkness of our sins into the light of grace. . . . .

The shadows fall.

The stars appear.

The birds begin to sleep.

Night embraces the silent half of the earth.

A vagrant, a destitute

wanderer with dusty feet, finds his way down

a new road. A homeless

God, lost in the night, without

papers, without

identifications, without even a num-

ber, a frail expendable

exile

lies down in desolation under the sweet stars of the world and entrusts

Himself to sleep.

--Thomas Merton, from "Hagia Sophia," 1963. Line length altered

. . . . I say that we are wound

With mercy round and round

As if with air . . . .

Be thou then, O thou dear

Mother, my atmosphere;

My happier world, wherein

To wend and meet no sin;

Above me, round me lie

Fronting my froward eye

With sweet and scarless sky . . . .

World-mothering air, air wild,

Wound with thee, in thee isled,

Fold home, fast fold thy child.

--Gerard Manley Hopkins

from "The Blessed Virgin Compared to the Air We Breathe"

The Peaceable Table is

a project of the Animal Kinship Committee of Orange Grove Friends Meeting, Pasadena, California. It is intended to resume the witness of that excellent vehicle of the Friends

Vegetarian Society of North America, The Friendly

Vegetarian, which appeared quarterly between 1982 and

1995. Following its example, and sometimes borrowing from its

treasures, we publish articles for toe-in-the-water

vegetarians as well as long-term ones, news notes, poetry, letters, book

and film reviews, and recipes.

The journal is intended to be

interactive; contributions, including illustrations, are

invited for the next issue. Deadline for the January 2009 issue

will be Dec. 29, 2008. Send to graciafay@gmail.com or 10 Krotona Hill, Ojai, CA 93023. We operate primarily

online in order to conserve trees and labor, but hard copy

is available for interested persons who are not online.

The latter are asked, if their funds permit, to donate $12 (USD) per year. Other

donations to offset the cost of the domain name and server are welcome.

Website: www.vegetarianfriends.net

Editor: Gracia Fay Ellwood

Book and Film Reviewers: Benjamin Urrutia & Robert Ellwood

Recipe Editor: Angela Suarez

NewsNotes Editors: Lorena Mucke and Marian Hussenbux

Technical Architect: Richard Scott Lancelot Ellwood

But what of those who never have such a lifegiving experience, or have numinous experiences that seem to give quite a different message? As William James remarks, a religious experience is not necessarily authoritative for those who have not had it. One can point out that there are all too many facts that seem utterly incompatible with Faith's sense of the presence of an all-nurturing Divine Mother. To give just one example: In eighteenth century London, an estimated one thousand infants were abandoned on the streets every year by desperate unwed mothers unable to support them, mothers themselves abandoned by lovers whom society essentially excused from taking responsibility. A parallel situation can be found in the ancient Roman world; according to law, the paterfamilias had the right to decree that any newborn he chose not to accept must be thrown out, exposed. (The abandoned babies were sometimes "rescued" by slave traders.) How can one say that these innocents, dying of cold, hunger, and fear, were nurtured by an all-loving and all-giving Divine Mother?

But what of those who never have such a lifegiving experience, or have numinous experiences that seem to give quite a different message? As William James remarks, a religious experience is not necessarily authoritative for those who have not had it. One can point out that there are all too many facts that seem utterly incompatible with Faith's sense of the presence of an all-nurturing Divine Mother. To give just one example: In eighteenth century London, an estimated one thousand infants were abandoned on the streets every year by desperate unwed mothers unable to support them, mothers themselves abandoned by lovers whom society essentially excused from taking responsibility. A parallel situation can be found in the ancient Roman world; according to law, the paterfamilias had the right to decree that any newborn he chose not to accept must be thrown out, exposed. (The abandoned babies were sometimes "rescued" by slave traders.) How can one say that these innocents, dying of cold, hunger, and fear, were nurtured by an all-loving and all-giving Divine Mother?  To return to the abandoned babies of London: in 1719 one Thomas Coram, who had had a successful career in the American colonies and at sea, came back to England. His expectations of enjoying the good life were brought up short by the horrifying scenes of dead and dying babies that he saw as he walked London streets on a cold winter morning. A man of action as well as compassion, Coram set about establishing an organization to rescue such victims. There was much accumulated wealth in the hands of the middle and upper classes, and he hoped to reach their hearts for his project.

To return to the abandoned babies of London: in 1719 one Thomas Coram, who had had a successful career in the American colonies and at sea, came back to England. His expectations of enjoying the good life were brought up short by the horrifying scenes of dead and dying babies that he saw as he walked London streets on a cold winter morning. A man of action as well as compassion, Coram set about establishing an organization to rescue such victims. There was much accumulated wealth in the hands of the middle and upper classes, and he hoped to reach their hearts for his project.

Lisa Couturier - environmental journalist, magazine editor, teacher --here writes movingly about the wildlife that can be found in the hidden wild spaces of the northeastern megalopolis stretching from Washington, DC, to New York City. It seems tremendously counterintuitive that such an abundance and variety of wild animals could manage to survive, and even thrive, in one of the world's most thickly urbanized areas. Yet here they are: owls, hawks, mice, pigeons, foxes, beavers, crows, snakes, geese, coyotes, vultures, and many others. Lisa loves them and knows that they are beings with hopes and dreams, with loves and families. She does not feel the contempt, fear and hatred that is all too common among humans towards these creatures.

Lisa Couturier - environmental journalist, magazine editor, teacher --here writes movingly about the wildlife that can be found in the hidden wild spaces of the northeastern megalopolis stretching from Washington, DC, to New York City. It seems tremendously counterintuitive that such an abundance and variety of wild animals could manage to survive, and even thrive, in one of the world's most thickly urbanized areas. Yet here they are: owls, hawks, mice, pigeons, foxes, beavers, crows, snakes, geese, coyotes, vultures, and many others. Lisa loves them and knows that they are beings with hopes and dreams, with loves and families. She does not feel the contempt, fear and hatred that is all too common among humans towards these creatures.  This tale is a fantasy that will warm the hearts and inspire the minds of both children and grownups who love animals. It tells the story of an unusual celebration of the Blessing of the Animals - an event that in real life takes place in many churches of various denominations on the Feast Day (October 4) of St. Francis of Assisi, that most Christian of Christians, who rightly saw all God's creatures as our brothers and sisters.

This tale is a fantasy that will warm the hearts and inspire the minds of both children and grownups who love animals. It tells the story of an unusual celebration of the Blessing of the Animals - an event that in real life takes place in many churches of various denominations on the Feast Day (October 4) of St. Francis of Assisi, that most Christian of Christians, who rightly saw all God's creatures as our brothers and sisters. This remarkable book -- a national bestseller -- begins and ends with the same grief, the death of Alex, the African Grey parrot who had been the author's companion and research associate for some thirty years. The story then circles back to show us why the passing of this little creature devastated not only Irene Pepperberg, but also his millions of fans throughout the world, admirers of the numerous popular features in print and on television in which he had starred. Early on, we learn of the author's emotionally deprived childhood; her failed marriage, her ricochet academic career as one institution of higher education after another proved unable or unwilling to accommodate her pioneering project, the great passion of her life: Alex and what he was teaching the world about animal intelligence.

This remarkable book -- a national bestseller -- begins and ends with the same grief, the death of Alex, the African Grey parrot who had been the author's companion and research associate for some thirty years. The story then circles back to show us why the passing of this little creature devastated not only Irene Pepperberg, but also his millions of fans throughout the world, admirers of the numerous popular features in print and on television in which he had starred. Early on, we learn of the author's emotionally deprived childhood; her failed marriage, her ricochet academic career as one institution of higher education after another proved unable or unwilling to accommodate her pioneering project, the great passion of her life: Alex and what he was teaching the world about animal intelligence.  Another dimension of Alex's mind was shown one day in 1998, when Irene Pepperberg stormed into the lab room very upset after a difficult academic meeting. The parrot, clearly able to pick up clues to her feelings, saw her and said "Calm down." Though she would otherwise have found this comment from a bird extraordinary, Irene, who was in no mood to live up to her first name, admits she did not respond accordingly but snapped, "Don't tell me to calm down!" and slammed into her office.

Another dimension of Alex's mind was shown one day in 1998, when Irene Pepperberg stormed into the lab room very upset after a difficult academic meeting. The parrot, clearly able to pick up clues to her feelings, saw her and said "Calm down." Though she would otherwise have found this comment from a bird extraordinary, Irene, who was in no mood to live up to her first name, admits she did not respond accordingly but snapped, "Don't tell me to calm down!" and slammed into her office.  From concentration camp survivor and novelist Elie Wiesel: "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented."

From concentration camp survivor and novelist Elie Wiesel: "Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented."  My experience with vegetarianism has gone through many phases. One of the most disturbing has been the response of Friends to this practice.

My experience with vegetarianism has gone through many phases. One of the most disturbing has been the response of Friends to this practice. In time we moved, our experience of Quakerism broadened and enlightened [during residence] in two other states. We grew closer to Friends as individuals and as the group expressions of faith in action. But until the youth movement introduced vegetarianism as a lifestyle that could not be ignored, we always found a sense of being loved and approved "in spite of our peculiar idiocy."

In time we moved, our experience of Quakerism broadened and enlightened [during residence] in two other states. We grew closer to Friends as individuals and as the group expressions of faith in action. But until the youth movement introduced vegetarianism as a lifestyle that could not be ignored, we always found a sense of being loved and approved "in spite of our peculiar idiocy."