He Came to Himself . . . .

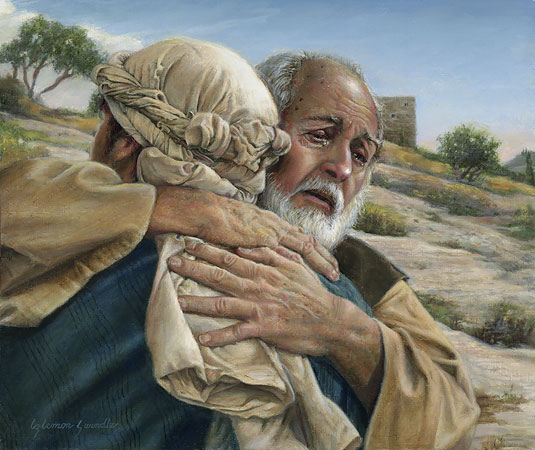

The editorial in the May, 2005 Peaceable Table dealt with the way people tend to be unaware of the lenses through which they see the world--specifically, various passages in the Bible that, to the majority of readers, seem obviously to endorse killing and eating animals. One example given was that favorite among Jesus' parables, the story of the Prodigal Son. In dealing with this parable again, I will focus on the theme of change of heart, i.e., the way the principal characters rejected a destructive way of life and "came to [themselves]." In Quaker terms, it is finding the Inner Light which has been occluded; or one could use other Christian or Jewish language of turning back from evil and returning to the image of God within.

The parable tells of a younger son who demands that his father give him his inheritance (implication: "I wish you were dead now"), then goes abroad to squander it in wild living. When it is all gone, the country is struck with famine, and the only job the erstwhile high-living youth can find is feeding pigs--the lowest of the low, according to the sensibilities of ancient Hebrews and some other cultures of that area. He becomes so hungry he wants to eat some of the pods the pigs eat. Finally, he "comes to himself" and realizes he would be better off going home, eating humble pie, and asking his father to take him back as a hired servant. But the father, who sees him coming at a great distance (implication: the father spent a lot of time gazing longingly down the road), cuts short his apology, has him dressed in expensive clothes and jewelry, and orders a slave to "kill the best calf" for a celebratory feast.

The older son, coming home from the fields and hearing the sounds of music and dancing, asks what is going on. But when he is told that this is his father's way of celebrating his brother's return, he angrily refuses to go in. So his father comes out to beg him to join the party. "Look," says the older son, "I've slaved away for you for all these years, but you never even gave me a kid with which to have a party with my friends. But when this son of yours comes back after wasting your money with whores, you kill the best calf for him."

"Son," replied the father, "You are always with me, and all that I have is yours. It was right for us to celebrate, for your brother was dead and is alive again."

The deep appeal of the story of course centers around this change of heart of the thoughtless, extravagant younger son, and the father's forgiving love. It is not hard to see the spiritual implications: however foolishly and recklessly we have lived, however much we have wounded the divine heart, if we "come to ourselves," return, we will be welcomed back into the embrace of boundless love and festal joy.

But around the edges of this story's luminous center remain some disturbing problems. Readers are so used to equating the father with God that they almost cease to see the story as a metaphor, the father as a human being who is like God in some ways and unlike God in others. Most do not notice that for this father's passionate love and capacity for joy to be unknown to both his sons despite all the years they have lived together means that there is something profoundly wrong with him. It seems he found it terribly hard to put his arms around his boys or say "I love you" (and there is apparently no mother in the picture); perhaps he could never express tenderness at all. And why did both of them feel so starved for joy and fun? It is clear that as the younger son was "coming to himself," the father had to do so as well. All that time he spent gazing down the road, and especially the ecstatic moment when he saw his ragged son in the distance trudging toward him, he was realizing how much he had loved his boy, and how intensely he now wanted to show it.

Major cultural evils are also evident in the story. It is told in a society under Roman rule in which, according to Dominic Crossan and other scholars, perhaps 90 - 95% of the people live on or over the edge of subsistence, in which confiscation of family land by the powerful elites as a result of tax indebtedness was causing more and more peasants to become day laborers, beggars, or slaves. This story's family is among the tiny minority that has amassed most of the resources; it has both hired servants, mistheoi, and slaves, douloi. To be both wealthy and innocent was nearly impossible; as one of Jesus' sayings has it, "it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God."

And, of course, the violence against animals is not only an element in the tale, it is emphasized; the characters even use the killing of a baby or juvenile animal as a synonym for feasting! But what about the terror and pain of the calf? What about the grief of the mother cow? It never occurs to the happy father, who orders a slave to kill a calf (or to the bitter older son who wanted to have a kid killed for a party) that the grieving--and silenced--mother cow/goat could never say "This my son was dead and is alive again."

Like all parables, this tale is brief, symbolic, suggestive; but it does not provide great psychological depth. A psychologically insightful commentary on it can be found in that darkest of Jane Austen's comedies, Mansfield Park, which also presents the theme of the returning prodigal.

Mansfield is the great estate of a wealthy English baronet, Sir Thomas Bertram, who owns additional property in Antigua in the West Indies. He was among the "haves" in another period, probably around 1808, in which the gap between rich and poor was widening, with confiscation of lands and much suffering and hunger among the "have-not's." Sir Thomas' mansion is "modern-built," which clues us in that his wealth is probably not inherited from a long line of forebears, but came within the past generation or so from slave labor on the Bertram sugar plantation. He also has political power, being a member of Parliament. Furthermore, Sir Thomas seems fortunate in his family; he has a harmonious marriage to a still-beautiful wife, and four handsome, highly-regarded grown children, as well as a sister-in-law and an adopted niece (Fanny Price, the story's main character) devoted to the Bertrams and working selflessly for them.

But like the father in the parable, Sir Thomas cannot express his love to his children. Neither does their mother; Lady Bertram is so passive as to be virtually as non-existent as the mother in Jesus' story. The only active mothering the two daughters receive is from their aunt, who flatters and spoils them, while she relentlessly bullies the insecure niece, Fanny. Sir Thomas is pleased with his daughters' high social achievements, but he is unaware that they have little or no moral fibre, and that his presence makes home a dull and suffocating place to them. He pays no attention to his sister-in-law's cruel abuse of Fanny.

But like the father in the parable, Sir Thomas cannot express his love to his children. Neither does their mother; Lady Bertram is so passive as to be virtually as non-existent as the mother in Jesus' story. The only active mothering the two daughters receive is from their aunt, who flatters and spoils them, while she relentlessly bullies the insecure niece, Fanny. Sir Thomas is pleased with his daughters' high social achievements, but he is unaware that they have little or no moral fibre, and that his presence makes home a dull and suffocating place to them. He pays no attention to his sister-in-law's cruel abuse of Fanny.

The older son, Tom, who is to inherit the estate, becomes the prodigal son, spending much of his time away from home: drinking, betting at horse races, and fettering himself with huge debts. In order to pay them, Sir Thomas has to make a major financial sacrifice, which will probably deprive the younger son, Edmund, a serious and well-meaning young man, of much of his expected income. Furthermore, the estate in Antigua is failing, probably due in part to the recent abolition of the slave trade, and Sir Thomas has to sail there and be absent from home for two years in order to make his plantation profitable again.

Exploitation of and violence against animals is of course part of the total picture, both the killing of domestic animals for food, and the killing of wild animals for sport by the young men in the story. While the father himself is not depicted as hunting, his general emotional numbness, reproduced in his sons and their friends in regard to animals, is clearly a prerequisite to finding it fun to kill harmless innocents.

Shortly after Sir Thomas returns (and puts an end to a questionable play the young people were rehearsing), the older daughter, Maria, desperate to escape from home, marries a man who is enormously wealthy, but so foolish and inept that she holds him in contempt. After only six months of marriage she leaves him for an adulterous affair with a man she had previously hoped to marry, Henry, who is also the brother of Edmund's sweetheart. (The younger daughter Julia also runs off, marrying a frivolous socialite.) Maria, then, becomes the prodigal daughter. This huge, malodorous scandal leads to the breakup of Edmund's romance and threatens to destroy the social standing of the Bertram family. Furthermore, it takes place shortly after Tom, abandoned by his worldly friends when he is injured and ill, is brought home and hovers between life and death.

During his long illness, Tom is nursed by the compassionate Edmund, the very brother whose financial future his gambling had threatened, and who would have inherited the estate had Tom died. As a result of his suffering and this undeserved brotherly love, the prodigal son comes to himself, recovers, and becomes a new and responsible person.

During his long illness, Tom is nursed by the compassionate Edmund, the very brother whose financial future his gambling had threatened, and who would have inherited the estate had Tom died. As a result of his suffering and this undeserved brotherly love, the prodigal son comes to himself, recovers, and becomes a new and responsible person.

Edmund comforts the child Fanny in her homesickness.

The family's catastrophes also cause Sir Thomas to come to himself. He realizes how egregiously he has failed his daughters, and also seems to become aware how he has wronged his niece Fanny. He is comforted by the change of heart in Tom, and by Edmund's strength. Perhaps the chief means of grace to Sir Thomas is Fanny, who suffered so greatly as a result of his oppressiveness and negligence; she accepts him as her father, and becomes the daughter of his heart. Fanny and Edmund also become means of healing to one another.

Like the father and the prodigal son in the parable, the family in Mansfield Park is embedded in the cultural evils of class oppression, human slavery, and abuse of animals. The novel, even more than the parable, shows that these evils are intertwined. Sir Thomas, the powerful lord of all he surveys, has been taught an outlook of emotional distance and unyielding control over his property, his human subjects, and his own feelings, and thus remains ignorant of what is going on in his daughters' hearts until inner pressures build to an explosion. Just as the prodigal in the parable reaches bottom and has to face himself, just as people in our society are faced today with the prophetic word about the cultural evils of violence against animals and the planet, and must choose, the book's characters must make a decision. Either they will deliberately continue down the destructive paths of their inherited lifestyle, or take the risk of acknowledging their complicity, coming to themselves, and venturing into an unknown new path. Both in the parable and the book, divine compassion and forgiveness flow out through human hearts to those who come to themselves.

But Jane Austen's characters are too genuinely human for her story to manifest anything like a perfect resolution. Sir Thomas never comes to terms with his complicity in human slavery. Neither Tom nor Edmund face up to their violence against animals, nor does Fanny condemn it, even though both Edmund and Fanny would very likely have encountered an impassioned prophetic word against it by a favorite poet, William Cowper (see Poetry section below). The prodigal daughter Maria finally leaves her unloving lover in angry frustration; but it is not evident that she comes to herself, and her father never really accepts her back. (Considering how a patriarchal society usually regards sexual violations by a woman, would the father in the parable have welcomed a prodigal daughter?) For that matter, the spiritual outcome for the bitter older son in the parable is not known, either.

God is with us--Immanuel--reaching out loving arms to welcome those who gather the courage to come to themselves and change their ways. But perfect fulfillment we are unlikely to see; alongside wonderful expressions of love and renewal, there will probably always be unanswered questions and unfulfilled hopes.

We must live in the in-between place, the place of waiting. We must work in faith and hope as we offer ourselves as a means to the enactment of compassionate divine love.

—Gracia Fay Ellwood

For a further analysis of cultural evils and change of heart in Mansfield Park, see www.jasna.org/persuasions/online/vol24no1/ellwood.html

Even if you don't desperately want to live to be 100, this book is for you. The subtitle puts it well: “How you can – at any age – dramatically increase your life span and your health span.” The author is John Robbins, onetime heir to the Baskin-Robbins ice cream empire who also authored the bestselling Diet for a New America and several other invaluable books.

Even if you don't desperately want to live to be 100, this book is for you. The subtitle puts it well: “How you can – at any age – dramatically increase your life span and your health span.” The author is John Robbins, onetime heir to the Baskin-Robbins ice cream empire who also authored the bestselling Diet for a New America and several other invaluable books.

¼ cup organic carob powder

¼ cup organic carob powder For years I boasted about my Cherokee blood. And my flippant remark about eating meat was: “Can you imagine an Indian saying, ‘I don’t eat meat, I’m a vegetarian’?” I laughed. I had said this knowing how sacred the buffalo was to the people and how the white man almost slaughtered the buffalo out of existence.

For years I boasted about my Cherokee blood. And my flippant remark about eating meat was: “Can you imagine an Indian saying, ‘I don’t eat meat, I’m a vegetarian’?” I laughed. I had said this knowing how sacred the buffalo was to the people and how the white man almost slaughtered the buffalo out of existence.

Of course the main element in his appeal to Christians as well as to many folk of other religions or none is his great and joyous love of the natural world, which in the last century caused him to become the patron saint of both the ecological and animal-defense movements.

Of course the main element in his appeal to Christians as well as to many folk of other religions or none is his great and joyous love of the natural world, which in the last century caused him to become the patron saint of both the ecological and animal-defense movements.