Editorial: Hearing Her Into Speech

For centuries, human beings have created stories in which they imagine animals talking in our speech, as the August PT editorial discussed. Sometimes, especially in so-called beast fables, the animal characters are little more than human beings in beast shape; in other cases, however, the author, out of a genuine desire to relate to other creatures, makes some degree of effort to think her/himself into the mind of an animal. This requires respect, openness, and patience.

In contrast to this ancient human desire to communicate with animals, human beings have also found certain forms of the exploitation of animals so important to them that they closed themselves off to opportunities for communication. As we have mentioned before in PT, C.S. Lewis is a good example of these two conflicting attitudes in the same person. In many ways a disciplined and compassionate man, who detested cruel experiments on animals, Lewis felt this ancient desire (he was particularly fond of mice), and out of it he created the magnetically appealing talking animals in his Narnia stories and his science fiction novel Out of the Silent Planet. But he also liked his bacon and eggs, apparently believed vegetarians were trendy modern ascetics, and, later in life, probably did not want to condemn his wife's hunting. He thought he could have his wondrous animal-human conversations and eat his bacon too. But he failed to notice the problems implicit in his world in which speaking animals, with no sense either of fellow-feeling or of danger to themselves, agree with humans that nonspeaking animals are fair game for food and "sport."

The Arrogant Eye

Lacking even Lewis' ambivalence, for centuries many representatives of the scientific establishment investigating animals have simply asserted, or assumed, that they do not have minds or personalities. (Charles Darwin was a notable exception.) This claim is of course the justification for excluding them from the circle of ethical consideration, and visiting any number of horrors upon them, in the name of the search for knowledge. The implied worldview is that the human experimenter is the lord, and  animals are the subjects. As Uncle Andrew Ketterley, the sorcerer seeking a way into other worlds in Lewis's The Magician's Nephew, says,

animals are the subjects. As Uncle Andrew Ketterley, the sorcerer seeking a way into other worlds in Lewis's The Magician's Nephew, says,

"I am the great scholar, the magician, the adept, who is doing the experiment. Of course I need subjects to do it on. . . . My earlier experiments were all failures. I tried them on guinea pigs. Some only died. Some exploded like little bombs--"

"It was a jolly cruel thing to do," said Digory who had once had a guinea pig of his own.

"How you do keep getting off the point!" said Uncle Andrew. "That's what the creatures were for. I bought them myself."

Uncle Andrew is a sorcerer and not a reductionistic scientist, but their outlooks are similar: the guinea pigs were essentially things, and interchangeable.

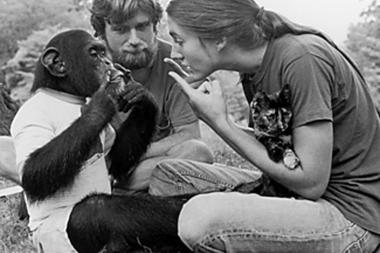

In contrast, when twenty-six-year-old Jane Goodall, innocent of university science courses, began observing the chimpanzees of Gombe in 1960, she approached them with respect, as beings in their own right. She found and recorded significant personality differences, and identified the chimps with names: David Greybeard, Goliath, Flo, Fifi, et. al. But when she developed her research data into a Ph.D. thesis at Cambridge a few years later, her professors would have none of this approach. The proper procedure was to identify one's animal subjects with numbers; to describe their actions as motivated by jealousy, or loyalty, or resentment, was anthropomorphizing. Behaviorism, a particularly extreme form of reductionism which still reigned unchallenged in animal studies in the 'Sixties, ruled that anthropomorphizing was one of the most heinous of scientific sins.

The professors intended to uphold scientific objectivity. Strict objectivity is not possible because we are always subjects, who have feelings and viewpoints. But what they sought includes emotional discipline, which is indeed necessary. Lacking critical understanding of themselves, they failed to notice what a huge emotional investment they and their kind had in regarding animals reductionistically. Reductionism is an aspect of the vision of "the arrogant eye which objectifies the other for its own benefit. . . . The Western elite have adopted this gaze: standing high on a hill, this sole Subject looks out on the world as its object," to quote theologian Sallie McFague. The arrogant eye wants to see what lies in its domain, but on its own terms: it determines which questions may be asked, and which are unacceptable. They didn't want to hear Goodall's answers because they had ruled out her questions, which threatened human sovereignty. (She cannily got around the taboos with circumlocutions such as "His behavior, if seen in humans, would be called jealousy.")

A Satellite Revolt

Patriarchy (or kyriarchy, the reign of the lords) is another aspect of the vision of the arrogant eye. The kyriarch determines what the nature of Woman is--a satellite to Man--and informs her what, as such, she is thinking and feeling, or ought to be. His message has varied somewhat over the centuries, and in different places. Throughout much of middle-class Western culture in the late 1940s, the 1950s and early 1960s, she was told that she found her fulfillment as the ever-attractive wife and mother in a nuclear family, keeping a clean, attractive house, meeting the needs of her high-achieving husband, and raising extravertive children. Any friendships with other women would be superficial, because she would feel essentially competitive with them.

Of the millions of women who swallowed this message, many found themselves discontented and confused. Why weren't they fulfilled? How had they failed? Why were their husbands so often preoccupied, or absent, or abusive? Why did they have such painfully mixed feelings toward their children? In feminist consciousness-raising groups of the 'Sixties and 'Seventies, middle-class women, rejecting the satellite image for one in which a woman had value in her own right, helped each other find answers. The process was sometimes referred to as "hearing her into speech." Instead of telling a woman what she was feeling and thinking, or ought to be, the intent of the members (not always carried out) was to listen respectfully and help her find out for herself who she was.

The approach of contemporary ethologists like Goodall, Marc Bekoff, and Jonathan Balcombe is essentially a process of hearing the animals into speech. The beasts will not speak English (or French, or Greek), and we will not understand them fully. Some speak "languages" more remote from ours than others. As philosopher Thomas Nagel said about bats, we humans find it hard to imagine ourselves into the mind of a being with poor vision that flies at dusk, uses sonar to catch and eat insects, and sleeps hanging upside down. Even with animals that are closer to us in the experiences of sleeping, food-seeking, mating, parenting, and the like, if we are hasty and undisciplined, we can misinterpret what they are thinking and feeling. But, says Balcombe, "Animals are not closed books, and their feelings are not unsolvable mysteries."

Like good scientists of any time, the ethologists observe and theorize with discipline and caution. But they do not bring to their task the arrogant eye but a caring and receptive one.

--Gracia Fay Ellwood

The term kyriarchy was coined by biblical critic Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza to acknowledge that powerful males dominate not only women but powerless men as well.

Sources: The Exultant Ark: A Pictorial Tour of Animal Pleasure by Jonathan Balcombe

"The Loving Eye and the Arrogant Eye" by Sallie McFague, in The Ecumenical Review, V. 49, Issue 2, p. 185

Thomas Nagel, "What is it Like to Be a Bat?" in Philosophical Review, LXXXIII 4 (October 1974): 435-50. See Bat

Lead Photo of Jonathan Balcombe and avian friend by Katherine Rose, Guardian News & Media Ltd

Drawing of Andrew Ketterley by Pauline Baynes

Photo of consciousness-raising group by Women's Movement

Archives, Women's Educational Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Unset Gems

The Scream

The worst scream I have ever heard: a mother cow on a dairy farm, as she screams and bellows for her stolen baby to be given back to her.

~ Gary Yourofsky, public speaker and activist

--Contributed by Lorena Mucke

Just read the latest issue of PT. I was especially intrigued by Robert's piece about animals talking in movies and television programs. There are two points I would like to add to his list of problems with this practice. Cartoons with talking animals very often give them human speech defects. The "hero" character is usually spared, but the animal who is considered the social "loser" is often given a lisp or stutter. As a child with a profound lisp, and having a brother with a stutter, I was not encouraged by seeing Daffy Duck, Porky Pig or Sylvester the Cat continually come out on the short end. All things considered, I marvel at how rarely my brother and I were called by these names by our peers. I'm sure many others with such speech impediments weren't so blessed with considerate pals.

Just read the latest issue of PT. I was especially intrigued by Robert's piece about animals talking in movies and television programs. There are two points I would like to add to his list of problems with this practice. Cartoons with talking animals very often give them human speech defects. The "hero" character is usually spared, but the animal who is considered the social "loser" is often given a lisp or stutter. As a child with a profound lisp, and having a brother with a stutter, I was not encouraged by seeing Daffy Duck, Porky Pig or Sylvester the Cat continually come out on the short end. All things considered, I marvel at how rarely my brother and I were called by these names by our peers. I'm sure many others with such speech impediments weren't so blessed with considerate pals. wild animals has a dark and dangerous side. Exotic animal rescue compounds all over the world are overflowing with castoff exotic animals which have been pets of those deluded into thinking they can be easily trained and cared for. Having worked for seven years at Carolina Tiger Rescue, I assure you, the results are heartbreaking, costly and enduring.

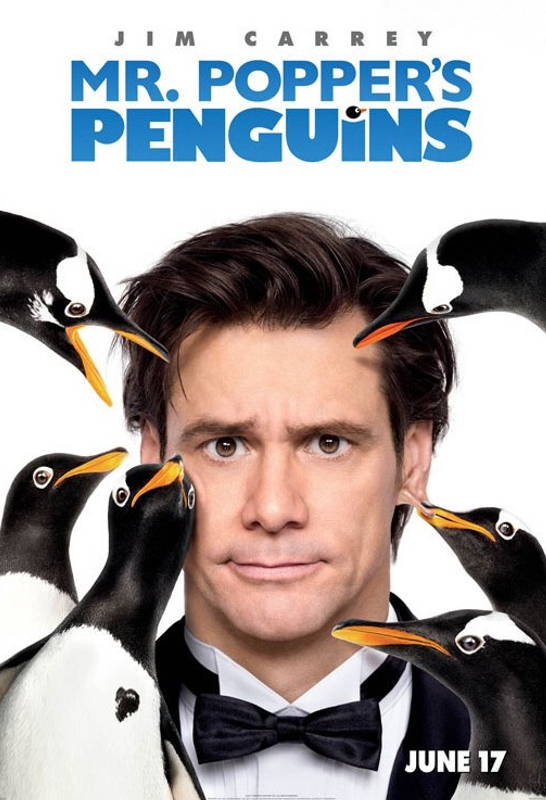

wild animals has a dark and dangerous side. Exotic animal rescue compounds all over the world are overflowing with castoff exotic animals which have been pets of those deluded into thinking they can be easily trained and cared for. Having worked for seven years at Carolina Tiger Rescue, I assure you, the results are heartbreaking, costly and enduring. In the novel, Mr. Popper is an absent-minded house-painter who daydreams of traveling to remote regions of the world, specially the Arctic and Antarctic. We are never told his first name; he is just "Mr. Popper." In the movie, he gets an upgrade in his profession - he is now a real estate agent - and a first name, Thomas "Tom" Popper Jr. On the other hand, the loyal and long-suffering wife in the book has become a (comfortably friendly) ex-wife in the movie.

In the novel, Mr. Popper is an absent-minded house-painter who daydreams of traveling to remote regions of the world, specially the Arctic and Antarctic. We are never told his first name; he is just "Mr. Popper." In the movie, he gets an upgrade in his profession - he is now a real estate agent - and a first name, Thomas "Tom" Popper Jr. On the other hand, the loyal and long-suffering wife in the book has become a (comfortably friendly) ex-wife in the movie.

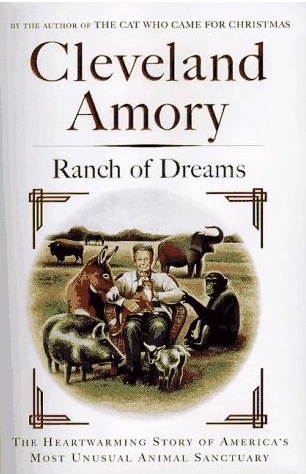

The late Cleveland Amory (1917-1998) was born and raised in the upper reaches of Bostonian society, including the right prep schools and, of course, Harvard. From this privileged vantage point, he wrote several delightful and informative books about Society when the word really meant something: The Proper Bostonians, The Last Resorts, and Who Killed Society?

The late Cleveland Amory (1917-1998) was born and raised in the upper reaches of Bostonian society, including the right prep schools and, of course, Harvard. From this privileged vantage point, he wrote several delightful and informative books about Society when the word really meant something: The Proper Bostonians, The Last Resorts, and Who Killed Society? rescues. These involved herds of animals otherwise scheduled to be shot: burros from the bottom of the Grand Canyon, goats from San Clemente in the California Channel Islands, wild horses in Nevada, bison in Montana, zoo and circus elephants. In some of these cases the targeted animals were considered an invasive species, threatening endangered indigenous life. But that was no fault of the burros, goats, or horses, nor did it lessen the dread of their prospective genocide.

rescues. These involved herds of animals otherwise scheduled to be shot: burros from the bottom of the Grand Canyon, goats from San Clemente in the California Channel Islands, wild horses in Nevada, bison in Montana, zoo and circus elephants. In some of these cases the targeted animals were considered an invasive species, threatening endangered indigenous life. But that was no fault of the burros, goats, or horses, nor did it lessen the dread of their prospective genocide. truly using language or something else has been, and still is, argued interminably by specialists, but what cannot be denied is that this chimpanzee had a very unusual life. Torn from his mother at birth, Nim was raised and trained at Columbia University, where a well-meaning series of student caretakers took him into their homes, dressing him in toddler clothes and letting him eat at the table with them. The idea was to raise the chimp as a human child, hoping he would then learn human language in the normal way.

truly using language or something else has been, and still is, argued interminably by specialists, but what cannot be denied is that this chimpanzee had a very unusual life. Torn from his mother at birth, Nim was raised and trained at Columbia University, where a well-meaning series of student caretakers took him into their homes, dressing him in toddler clothes and letting him eat at the table with them. The idea was to raise the chimp as a human child, hoping he would then learn human language in the normal way. Slice cucumbers in a food processor.

Slice cucumbers in a food processor. The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls

The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls