My Journey of Transformation

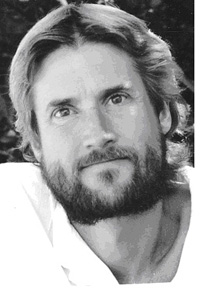

I was born into a typically heavy meat and dairy-eating family in New England in the early 1950s, but fortunately discovered the joy of vegetarianism when I was just 22. Looking back, I can see there were some significant experiences that planted in me the seeds of vegan living. For example, one seed experience from my childhood that stands out vividly, and that I am grateful for having helped awaken my heart, is witnessing the killing of a cow on an idyllic Vermont dairy farm. I was about twelve years old, and attending a summer camp in the Green Mountains called Camp Challenge.

I was born into a typically heavy meat and dairy-eating family in New England in the early 1950s, but fortunately discovered the joy of vegetarianism when I was just 22. Looking back, I can see there were some significant experiences that planted in me the seeds of vegan living. For example, one seed experience from my childhood that stands out vividly, and that I am grateful for having helped awaken my heart, is witnessing the killing of a cow on an idyllic Vermont dairy farm. I was about twelve years old, and attending a summer camp in the Green Mountains called Camp Challenge.

The camp was affiliated with an organic farm in the valley below us where we would sometimes work baling or weeding. At one point all of us boys went down there. There were horses and cows and fields of beans and wheat under a beautiful blue sky, and we were brought to the barn where a cow was standing alone, in the middle of the wooden floor. She was one of the dairy cows, and Tom (the owner-director of the camp and the farm, a handsome Dartmouth-educated outdoorsman we all admired enormously) informed us that she could not give enough milk and we would therefore be using her for meat. He held a rifle in his hand and pointed to a precise spot on her head where the bullet would have to hit so that she would fall. Then he aimed and fired. I was astounded as the cow instantly crashed to the floor, feces and urine gushing from her rear near where I stood. Tom immediately grabbed a long knife, jumped astride her prostrate body, and with a great strong stroke, cut her head almost completely off. I was amazed at how far the blood shot out of her open neck, propelled by her still-beating heart, long red liquid arcs flying far through the air and splattering all around us as her body convulsed on the blood-soaked floor. We all watched silently as she finally stopped moving and bleeding, and many of us had to wipe our blood-spattered arms and legs. While I stood in shock and horror at what I had just witnessed, Tom wiped his brow and calmly explained that the meat would be no good if her heart didn’t pump the blood out of her flesh; it would be soggy and useless. We spent the next hour or so disemboweling her body, and finally got the large edible parts into the back of a truck to be taken to a butcher; we would eat her flesh for the rest of the month. Some of the boys took souvenirs: teats, tail, eyes, brain.

For ten more years, I continued, undaunted, to eat the flesh, milk, and eggs of animals. I simply did not know one could survive without doing so, and I had never met anyone who ate a plant-based diet. When I went away to Colby College in Maine and heard of vegetarianism, something inside me was kindled, but I did not yet question my fundamental eating habits.

In 1974, in my junior year, I heard of The Farm in Tennessee, a relatively newly formed spiritual community of about eight hundred people, mainly from San Francisco. One of the things that intrigued me most about The Farm was that everyone there was a vegetarian. It was a vegan community, actually (though that word was not yet in commerce), for they were vegetarian not for health reasons, but for ethical and spiritual reasons, and they ate no animal products whatsoever, not even eggs, dairy products, or honey. I had yet knowingly even to meet a vegetarian in my life at that point, but I saw in the books published by The Farm pictures of happy, healthy-looking and highly creative people living with a mission to demonstrate a more sustainable and harmonious way of living. I did my senior thesis in Organizational Behavior on The Farm, examining the theory and practice of a community based on cooperation rather than competition, and compassion rather than oppression. It was an eye- and heart-opening project for me. Their purpose was clearly stated: “We’re here to help save the world!”

Right after graduating from Colby, my brother Ed and I decided to go on a pilgrimage in search of spiritual understanding. We ended up walking for many months with no money from New England and eventually reached Alabama, going 15 to 20 miles a day on small back-country roads. At one point a friendly man directed us to a quaint little summer cabin on a stream where he said we could spend a few quiet days if we wanted to. We walked there and settled in, but there was no food sowe started foraging; and since there were fishing poles there, I decided to catch a few fish.

I put the first fish I caught into my raincoat pocket, and the second into the other, confident they would die before too long. I went back to the cabin to cook supper, quite proud of myself. The cattail roots and wild carrots we had gathered were cooking and I went to clean the fish, but to my dismay they were both still alive and flipping about convulsively. The old patterns kicked in and I grabbed one and slammed him down hard against the floor. Like waking from a nightmare, I could not believe what I was doing. Yet I did not think I could stop. The fish was still alive! Two more times I had to slam him against the floor, and then the other fish as well, before I could clean them, cook them, and we could eat them for dinner.

I could feel their terror and pain, and the violence I was committing against these unfortunate creatures, and I vowed never to fish again. The old programming that they were “just fish” completely fell away, and I saw with fresh eyes what was actually happening. Here I was on a spiritual pilgrimage, trying with all my heart to directly understand the deeper truths of being, yet I was acting contrary to this by first tricking the fish with a lure hiding a cruel barbed hook, and then killing them.

The next day Ed and I walked on, and though I still knew little about being a vegetarian, I began to think it would be a better—even a necessary—way to live. We eventually reached The Farm and stayed there several weeks. The experience absolutely sealed my vegetarianism and was worth the months of walking that it took to get there. Close to a thousand people, mostly living as married couples with kids in self-built homes, had created a community on a large piece of beautifully rolling farm and forest land. It was set up legally as a monastery, and it was strictly vegan to avoid harming animals, people, and the environment. The Farm had its own school, telephone system, soy dairy, publishing company, and Plenty, a blossoming outreach program that provided vegan food and health-care services both in Central America and in the ghettos of North America. Stephen Gaskin, the spiritual leader, was a student of Zen master Suzuki Roshi, founder of the San Francisco Zen Center.

The food was delicious, the atmosphere unlike anything I had ever experienced. People were friendly, energetic, bright, and there was a powerful sense of purpose: of working to create a better world. The soy dairy made tofu, soy milk, soy burgers, and “Ice Bean,” the first soy ice cream, and the schoolhouse for the children served all vegan meals. The kids, vegan from birth, grew tall, strong, and healthy. Gardens, fields, and greenhouses provided food for everyone, and people worked on different crews, building, cooking, teaching, and together making The Farm remarkably self-reliant. I worked in the book printing house.

After several weeks, we decided to continue our journey, walking south eventually to a Korean Zen Center we discovered in Huntsville, Alabama. The Zen training I undertook there led in 1984, nine years later, to my traveling to South Korea with shaved head and robes to live as a Zen monk in an ancient Zen monastery. Though I was a vegetarian, it took this second experience of living in a vegan community to deepen my understanding and commitment to vegan living.

I participated in the summer’s three-month intensive retreat. We rose at 2:40 a.m. to begin the day of meditation, practicing silence and simplicity, and eating vegan meals of rice, soup, vegetables, and occasional tofu, and retiring after the evening meditation at 9:00 p.m. The roots of this Korean Zen community in veganism and nonviolence went back about 600 years. . There was no silk or leather in any clothing, and it was absolutely not an option to kill even an insect. We simply used a mosquito net in the meditation hall. Through the months of silence and meditation, sitting still for seemingly endless hours, a deep and joyful feeling emerged within, a sense of solidarity with all life and of becoming more sensitive to the energy of situations.

When after four months I returned to the bustle of American life, I felt a profound shift had occurred, and the vegetarianism I’d been practicing for about eight years transformed spontaneously and naturally into veganism with roots that felt as if they extended to the center of my heart. Until then, I had mistakenly thought that my daily vegan purchases of food, clothing, and so forth were my personal choices. Now I could clearly see that not treating animals as commodities was not an option or a choice, for animals simply are not commodities. It would be as unthinkable to eat or wear or justify abusing an animal as it would be to eat or wear or justify abusing a human. The profound relief and empowerment of completely realizing and understanding this in my heart has been enriching beyond words.

—Will Tuttle

Will Tuttle, Ph.D., composer, pianist, and former Zen monk, is co-founder of Karuna Music and Art and the Prayer Circle for Animals, and is author of The World Peace Diet (Lantern Books, 2005, available at willtuttle.com/WPD.htm.), from which this essay is adapted. Will's book is reviewed in the November 2005 issue of PT.

Letter

Dear Editor,

Quite a lot of Friends here in Eastern Europe are vegetarian. At some gatherings we have a special table for ourselves at meals, so we can see the proportions. Maybe between a fifth and a third of the whole number of participants. I imagine that it is higher among youth. British Yearly Meeting claims that at their youth gatherings they only bother to serve vegetarian fare. Certainly at the German Yearly Meeting in Bad Pyrmont (near Hannover), which we just returned from on Monday, they arranged for dining at a nearby institutional cafeteria which offered mostly vegetarian food.

Quite a lot of Friends here in Eastern Europe are vegetarian. At some gatherings we have a special table for ourselves at meals, so we can see the proportions. Maybe between a fifth and a third of the whole number of participants. I imagine that it is higher among youth. British Yearly Meeting claims that at their youth gatherings they only bother to serve vegetarian fare. Certainly at the German Yearly Meeting in Bad Pyrmont (near Hannover), which we just returned from on Monday, they arranged for dining at a nearby institutional cafeteria which offered mostly vegetarian food.

Poland in general, as you might suppose, is not very vegetarian, and some people are quite anti-vegetarian. However, youth are very sympathetic to it, and we now have two vegetarian restaurants in Poznan (a city about the size of Pittsburgh) and two almost completely vegetarian health-food stores. Even cheese with microbacteriological rennet has penetrated our ordinary supermarkets. In Western Europe that would be no news, but in Eastern Europe it is very encouraging indeed.

Although I am a vegetarian mostly for ethical and spiritual reasons, it is interesting to observe that although as a young child (and enthusiastic carnivore) I had serious pernicious anemia and was in general sickly, after I became a vegetarian at around the time I entered college, I never required a doctor's treatment for anything at all, and have only had medical absences from work at the rate of about one day in five years. So I am a bit miffed when Poles assure me that I must have a horrible iron deficiency, existing on a vegetarian diet! It is one of their pet ideas.

I have had a chance to read more of your back issues since I first wrote you, and I am impressed by the way you and your team deal with hard issues in such a competent way, and all of the interesting information and reviews you gather and present. The recipes too are very practical, while the simple and attractive format is highly pleasing. Thank you again. I shall from time to time be holding you all in the Light. Keep up the good work!

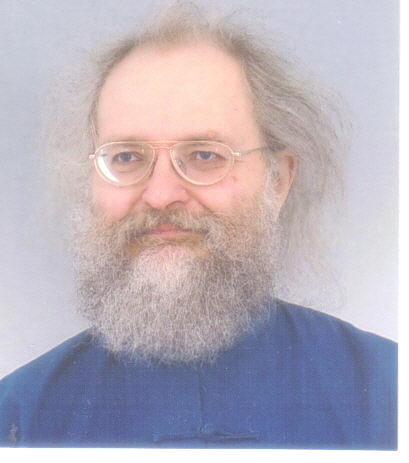

In Friendship,

Bradius Maurus III

Opponents of Canada's seal hunt have a powerful ally in their bid to end the annual slaughter: Paul McCartney, who pledged to take to the ice floes Thursday and frolic with the doe-eyed pups before the harvest gets under way. The former Beatle and his wife, Heather Mills McCartney, arrived Wednesday night in this fishing community on Canada's Atlantic coast and intend to land a helicopter on the ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence if Thursday's weather permits. The longtime animal-rights activists want to publicize the plight of the fluffy white pups, which are calved and weaned from their mothers on the frigid ice before being clubbed to death.

Opponents of Canada's seal hunt have a powerful ally in their bid to end the annual slaughter: Paul McCartney, who pledged to take to the ice floes Thursday and frolic with the doe-eyed pups before the harvest gets under way. The former Beatle and his wife, Heather Mills McCartney, arrived Wednesday night in this fishing community on Canada's Atlantic coast and intend to land a helicopter on the ice in the Gulf of St. Lawrence if Thursday's weather permits. The longtime animal-rights activists want to publicize the plight of the fluffy white pups, which are calved and weaned from their mothers on the frigid ice before being clubbed to death. . . . . [W]onderful news of a spectacular victory for the Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia . . .! For nearly a decade, we [of the National Resources Defense Council] have waged an all-out campaign to win government protection of this vast coastal temperate rainforest that is home to the Spirit Bear, a rare white-colored black bear, and other populations of endangered wildlife.

. . . . [W]onderful news of a spectacular victory for the Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia . . .! For nearly a decade, we [of the National Resources Defense Council] have waged an all-out campaign to win government protection of this vast coastal temperate rainforest that is home to the Spirit Bear, a rare white-colored black bear, and other populations of endangered wildlife. Do animals ever act out of sheer compassion for another living being, as over against self-interest or “instinct” – whatever exactly that means? Many would say no, that compassion is solely a human trait – unless they have known animals who proved that presumption wrong, or unless they have read these two eye-opening books. In both, von Kreisler has assembled case after case of animals who have helped and saved, often at great risk to themselves. The cases come from newsmedia reports, from interviews, from animal organizations, from the writings of others, and in the second book, Beauty in the Beasts, from the emailed, faxed, and mailed accounts that poured in from readers of The Compassion of Animals. Her animal heroes acted for the saving of others when, by any kind of human comprehension, no reason is apparent except love and loyalty, or plain fellow-feeling, as to why they should extend a helping hand, or paw, or life to one of another species – in the case of humans, a species that has not always served animals as well.

Do animals ever act out of sheer compassion for another living being, as over against self-interest or “instinct” – whatever exactly that means? Many would say no, that compassion is solely a human trait – unless they have known animals who proved that presumption wrong, or unless they have read these two eye-opening books. In both, von Kreisler has assembled case after case of animals who have helped and saved, often at great risk to themselves. The cases come from newsmedia reports, from interviews, from animal organizations, from the writings of others, and in the second book, Beauty in the Beasts, from the emailed, faxed, and mailed accounts that poured in from readers of The Compassion of Animals. Her animal heroes acted for the saving of others when, by any kind of human comprehension, no reason is apparent except love and loyalty, or plain fellow-feeling, as to why they should extend a helping hand, or paw, or life to one of another species – in the case of humans, a species that has not always served animals as well.  We know that violence afflicts us at every level of existence: from the individual act to war, which is murder on a large scale. What is its origin, its causes? How can it be prevented, contained, defused, resolved?

We know that violence afflicts us at every level of existence: from the individual act to war, which is murder on a large scale. What is its origin, its causes? How can it be prevented, contained, defused, resolved? These are Hiassen's first and second novels for young readers. The hero of the first, Roy Eberhardt, is a transplant to Florida from Montana, and not too happy--at first--about the move. The second's hero, Noah Underwood, by contrast, is a Florida native with deep roots in the Sunshine State, going back at least to his piratical smuggler grandfather, and perhaps even deeper.

These are Hiassen's first and second novels for young readers. The hero of the first, Roy Eberhardt, is a transplant to Florida from Montana, and not too happy--at first--about the move. The second's hero, Noah Underwood, by contrast, is a Florida native with deep roots in the Sunshine State, going back at least to his piratical smuggler grandfather, and perhaps even deeper. 1 large yellow onion, finely chopped

1 large yellow onion, finely chopped 2 cups organic unbleached flour

2 cups organic unbleached flour I was born into a typically heavy meat and dairy-eating family in New England in the early 1950s, but fortunately discovered the joy of vegetarianism when I was just 22. Looking back, I can see there were some significant experiences that planted in me the seeds of vegan living. For example, one seed experience from my childhood that stands out vividly, and that I am grateful for having helped awaken my heart, is witnessing the killing of a cow on an idyllic Vermont dairy farm. I was about twelve years old, and attending a summer camp in the Green Mountains called Camp Challenge.

I was born into a typically heavy meat and dairy-eating family in New England in the early 1950s, but fortunately discovered the joy of vegetarianism when I was just 22. Looking back, I can see there were some significant experiences that planted in me the seeds of vegan living. For example, one seed experience from my childhood that stands out vividly, and that I am grateful for having helped awaken my heart, is witnessing the killing of a cow on an idyllic Vermont dairy farm. I was about twelve years old, and attending a summer camp in the Green Mountains called Camp Challenge.  Quite a lot of Friends here in Eastern Europe are vegetarian. At some gatherings we have a special table for ourselves at meals, so we can see the proportions. Maybe between a fifth and a third of the whole number of participants. I imagine that it is higher among youth. British Yearly Meeting claims that at their youth gatherings they only bother to serve vegetarian fare. Certainly at the German Yearly Meeting in Bad Pyrmont (near Hannover), which we just returned from on Monday, they arranged for dining at a nearby institutional cafeteria which offered mostly vegetarian food.

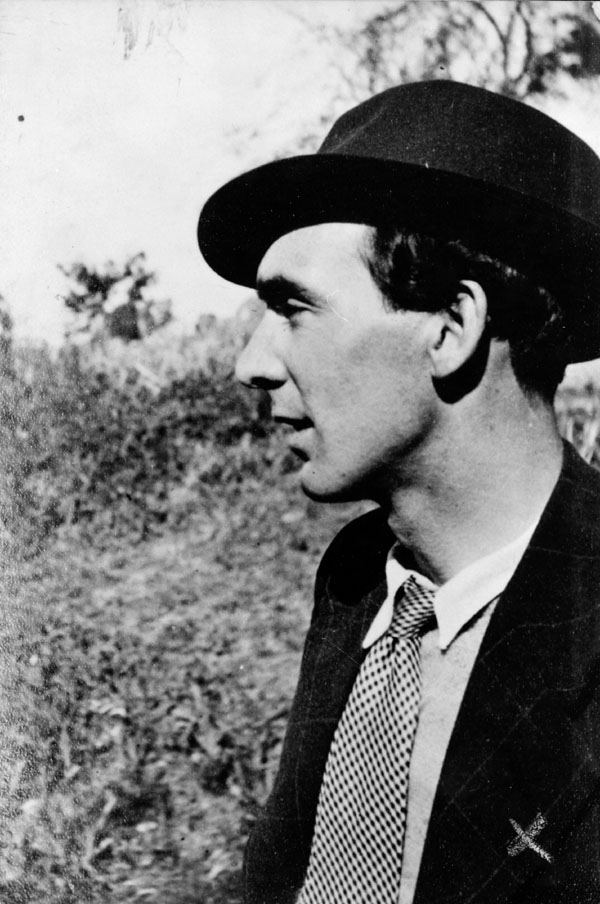

Quite a lot of Friends here in Eastern Europe are vegetarian. At some gatherings we have a special table for ourselves at meals, so we can see the proportions. Maybe between a fifth and a third of the whole number of participants. I imagine that it is higher among youth. British Yearly Meeting claims that at their youth gatherings they only bother to serve vegetarian fare. Certainly at the German Yearly Meeting in Bad Pyrmont (near Hannover), which we just returned from on Monday, they arranged for dining at a nearby institutional cafeteria which offered mostly vegetarian food. Albert Schweitzer, known primarily as a humanitarian whose thought and work were summarized in the phrase “reverence for life,” was in fact a pioneer in several fields, all of which were laced together to form and support his outlook. He was born into a musically gifted clergy family in Alsace in 1875; his parents were caring people who lived their faith and cherished their children. Nevertheless, from childhood he was deeply distressed at the suffering that he witnessed. In Memories of Childhood and Youth, he says “I used to suffer particularly because the poor animals must endure so much pain and want. The sight of an old, limping horse being dragged along by one man while another man struck him with a stick as he was being driven to the Colmar slaughterhouse--haunted me for weeks.” Schweitzer believed that we are in solidarity both with the abuser and the victim: “While so much ill-treatment of animals goes on, while the moans of thirsty animals in railway trucks sound unheard, while so much brutality prevails in our slaughterhouses . . . we all bear guilt.” Thus right activism on behalf of the suffering is carried out not in a spirit of indignant judgmentalism, but as a form of atonement for one’s own participatory guilt.

Albert Schweitzer, known primarily as a humanitarian whose thought and work were summarized in the phrase “reverence for life,” was in fact a pioneer in several fields, all of which were laced together to form and support his outlook. He was born into a musically gifted clergy family in Alsace in 1875; his parents were caring people who lived their faith and cherished their children. Nevertheless, from childhood he was deeply distressed at the suffering that he witnessed. In Memories of Childhood and Youth, he says “I used to suffer particularly because the poor animals must endure so much pain and want. The sight of an old, limping horse being dragged along by one man while another man struck him with a stick as he was being driven to the Colmar slaughterhouse--haunted me for weeks.” Schweitzer believed that we are in solidarity both with the abuser and the victim: “While so much ill-treatment of animals goes on, while the moans of thirsty animals in railway trucks sound unheard, while so much brutality prevails in our slaughterhouses . . . we all bear guilt.” Thus right activism on behalf of the suffering is carried out not in a spirit of indignant judgmentalism, but as a form of atonement for one’s own participatory guilt.  Dog, dog in my manger, drag at my heathen

Dog, dog in my manger, drag at my heathen